A DevOps Guide on How to Install Software in Linux

Learn how to optimize your cloud spend with Server Scheduler.

Learn how to optimize your cloud spend with Server Scheduler.

Contents

Ready to Slash Your AWS Costs?

Stop paying for idle resources. Server Scheduler automatically turns off your non-production servers when you're not using them.

Understanding the Linux Software Ecosystem

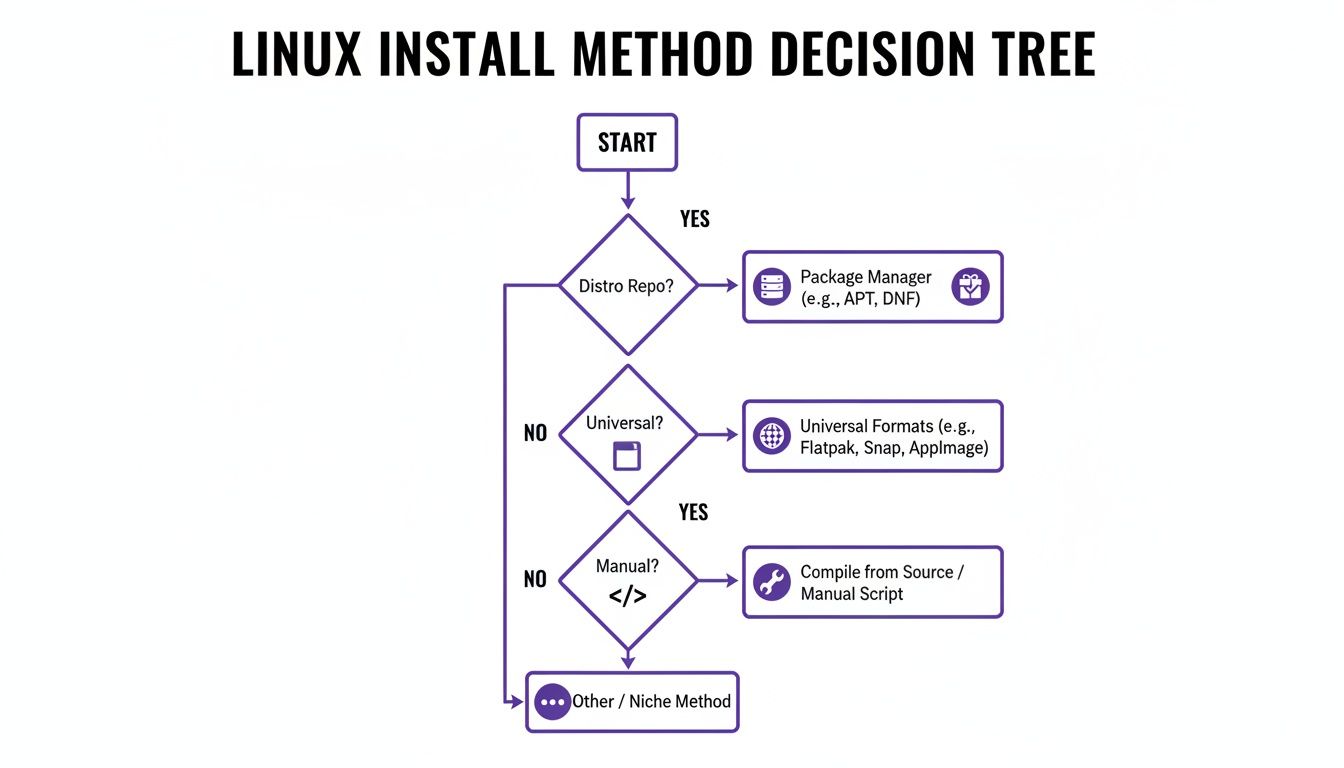

The foundation of Linux software management rests on repositories. Think of these as massive, curated app stores tailored for your specific Linux distribution, whether it's Debian, Arch, or a Red Hat derivative. When you issue a command like sudo apt install firefox, your package manager securely connects to these repositories, finds the requested software, verifies its integrity, and installs it. This model is a game-changer for security and stability because every package has been tested and approved by the distribution's maintainers.

A crucial part of this process is automatic dependency resolution. Most applications rely on other libraries and tools to function correctly. Instead of making you hunt down these dependencies manually, the package manager identifies and installs them for you. This prevents the "DLL hell" common on other operating systems and ensures a clean, functional installation every time. Different Linux families have their own preferred package managers: Debian-based systems like Ubuntu use apt, Red Hat-based systems like Fedora use dnf, and Arch-based systems rely on pacman. This structured, reliable approach is a major reason why Linux dominates the server world.

Getting Hands-On with Core Package Managers

Getting Hands-On with Core Package Managers

Mastering your distribution's package manager is a non-negotiable skill for any DevOps professional or system administrator. It's the command-line workhorse for building repeatable and reliable server environments. On Debian or Ubuntu systems, apt is your primary tool. Before installing anything, it's critical to update your local package list with sudo apt update. This command syncs with the repositories to learn about the latest available versions. Once updated, you can search for a package with apt search <package-name> and install it using sudo apt install <package-name>. apt provides a helpful summary of all the packages it will install, including dependencies, and asks for confirmation before proceeding.

In the Red Hat world (Fedora, CentOS), dnf serves the same purpose with a very similar syntax. You can find software with dnf search <package-name> and install it with sudo dnf install <package-name>. Like apt, dnf handles dependency resolution automatically and presents a transaction summary before making changes. For those on Arch Linux, pacman is the fast and efficient tool of choice. Its syntax is more concise, using flags like -S for installation (sudo pacman -S <package-name>) and -Ss for searching (pacman -Ss <package-name>). A common first step on Arch is to synchronize repositories and upgrade all packages at once with sudo pacman -Syu. While the commands differ slightly, the underlying principle is the same: a powerful tool managing software from trusted sources.

Using Universal Package Formats for Simplicity

Using Universal Package Formats for Simplicity

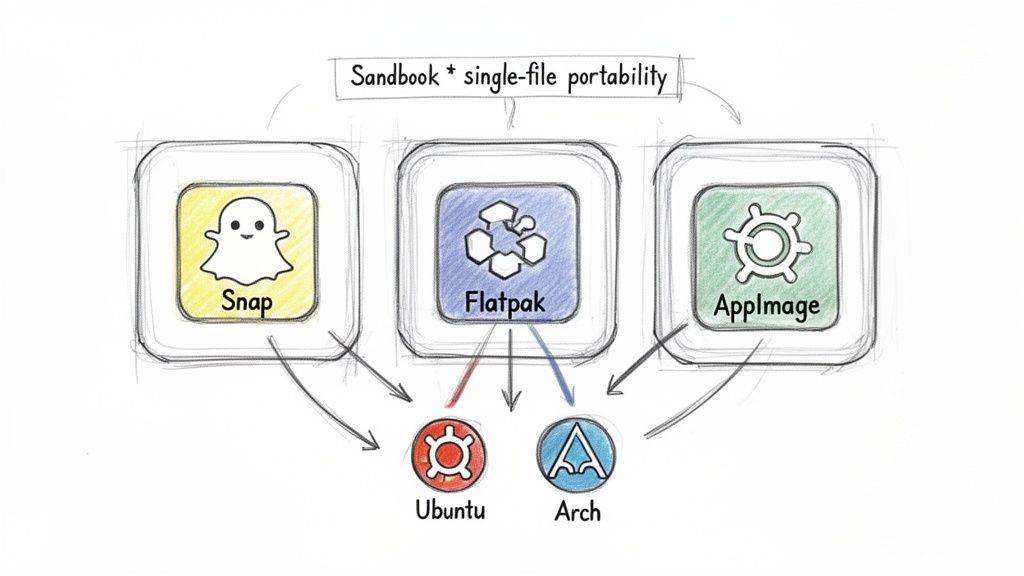

While traditional package managers are tied to specific distributions, a newer wave of universal package formats aims to solve the "it works on my machine" problem. Tools like Snap, Flatpak, and AppImage bundle an application with all of its dependencies into a single, self-contained package. This allows a developer to distribute one file that runs on nearly any Linux system, from Ubuntu to Fedora to Arch. Snaps, developed by Canonical, are particularly popular for their automatic background updates and rollback features, which are invaluable for server and IoT applications.

Flatpak's main advantage is its focus on security through sandboxing. Each Flatpak application runs in an isolated environment, preventing it from accessing your personal files or altering the host system without explicit permission. This is a significant security benefit for desktop users installing third-party software. AppImage offers the ultimate portability; it's a single executable file that requires no installation or administrator privileges. You simply download it, make it executable, and run it. This is ideal for trying new software without cluttering your system. These formats have made desktop Linux more accessible and are a key reason for its growing adoption.

| Format | Key Feature | Best For | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snap | Automatic updates & rollbacks | Server applications, IoT devices, and ensuring software is always current. | Managed via the snapd service and the snap command. |

| Flatpak | Security through sandboxing | Desktop applications where isolating processes is a priority. | Managed via the flatpak command and repositories like Flathub. |

| AppImage | Portability & no installation | Trying out new software, portable apps, and use cases without admin rights. | Managed manually by the user; each app is a standalone file. |

Performing Manual Installations with Confidence

Sometimes, you need to install software that isn't in your distribution's repositories. This is common for proprietary applications like Google Chrome or Slack, which are often distributed as local .deb (for Debian/Ubuntu) or .rpm (for Fedora/Red Hat) files. You can install these using lower-level tools like dpkg (sudo dpkg -i package.deb) or rpm (sudo rpm -ivh package.rpm). The major caveat is that these tools do not automatically resolve dependencies. If the package requires a library you don't have, the installation will fail. Thankfully, there's an easy fix on Debian-based systems: running sudo apt --fix-broken install will prompt apt to find and install all the missing dependencies for you.

For the ultimate control, you can compile software from source code. This method is essential when you need the very latest version of a tool, require a custom feature, or need to apply a patch. The process typically involves downloading a source code archive (e.g., a .tar.gz file), extracting it, and running three classic commands in the terminal: ./configure (to check your system for dependencies), make (to compile the code), and sudo make install (to copy the compiled files to the correct system directories). While this gives you maximum flexibility, it also means your system's package manager won't know the software exists, making uninstallation and updates a manual process.

Automating Software Deployment in DevOps

In a DevOps environment, manually installing software across dozens or hundreds of servers is inefficient and prone to error. Automation is the only scalable solution. The journey often begins with shell scripts, which can perform unattended installations by using flags like -y with apt or dnf to automatically confirm prompts. However, for true reliability, DevOps professionals turn to Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tools like Ansible. Instead of writing procedural scripts, Ansible uses declarative YAML playbooks to define the desired state of a system.

Ansible connects to your servers, checks their current state, and only performs the actions necessary to achieve the state defined in your playbook. This idempotent nature means you can run the same playbook multiple times without causing unintended changes. A well-written playbook serves as both automation and documentation, creating a single source of truth for your server configurations. This approach eliminates configuration drift and makes deployments predictable, scalable, and resilient—cornerstones of modern DevOps practice. For teams managing complex environments, understanding the broader landscape of automation is key. You can explore a variety of powerful options in our guide to the top cloud infrastructure automation tools.

Frequently Asked Questions

Even with a good grasp of the basics, some common questions often arise. Many users notice both apt and apt-get in tutorials. The simple rule is to use apt for interactive terminal use, as it offers a more user-friendly experience with features like a progress bar. For scripting and automation, stick with apt-get, as its output is designed for stability and backward compatibility. If you're ever unsure which package manager your system uses, you can identify the operating system with cat /etc/os-release.

Another common concern is the safety of installing software from outside official repositories. While official repos are vetted for security and stability, third-party sources like PPAs carry inherent risk. You are trusting the third-party developer completely, so you should only add repositories from sources you know and trust. Finally, if you encounter dependency errors, especially after a manual .deb installation, the command sudo apt --fix-broken install is your best friend. It instructs apt to find and install any missing dependencies, resolving the issue in most cases.