Hardware Load Balancer vs Software Load Balancer: Which is Right For You?

The core difference boils down to this: a hardware load balancer is a specialized, high-performance physical appliance built for one purpose—managing massive traffic with extremely low latency. In contrast, a software load balancer is a flexible application that runs on standard commodity hardware, offering the agility essential for modern cloud environments. Your choice hinges on whether you prioritize raw, predictable performance or dynamic, cost-effective scalability.

Stop wasting time on manual server management. Server Scheduler lets you automate resource scheduling with a simple point-and-click interface, helping you cut cloud costs and streamline operations.

Try it for freeContents

Ready to Slash Your AWS Costs?

Stop paying for idle resources. Server Scheduler automatically turns off your non-production servers when you're not using them.

Understanding The Core Architectural Differences

When comparing a hardware load balancer to a software load balancer, you are examining two fundamentally different philosophies. It’s the classic distinction between a purpose-built machine and an adaptable, flexible program. This single difference influences everything else, from raw performance and cost to how you manage and scale your infrastructure.

A hardware load balancer is a physical box that you can install in a data center. It's a proprietary appliance engineered from the ground up to perform one task exceptionally well: processing network traffic at blistering speeds. Internally, it contains specialized hardware like Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) designed specifically to forward packets with minimal latency. This focused design makes them incredibly powerful and predictable. Since dedicated silicon handles the heavy lifting, they can manage massive throughput without consuming CPU cycles from the application servers they protect. For years, this made them the preferred choice for large enterprises with substantial, predictable traffic loads.

In contrast, a software load balancer is simply an application that runs on commodity hardware, such as standard servers, virtual machines (VMs), or even containers. This software-first approach completely transforms how you manage traffic. Instead of a physical appliance, you have a piece of code that can be deployed almost anywhere. It integrates directly into your application stack and often becomes a key component of a modern, cloud-native ecosystem. Many software load balancers are essentially sophisticated reverse proxies, and understanding proxy technology is essential to grasping their operation. For a deeper dive, you can explore how to build a proxy server.

Comparing Performance And Scalability Models

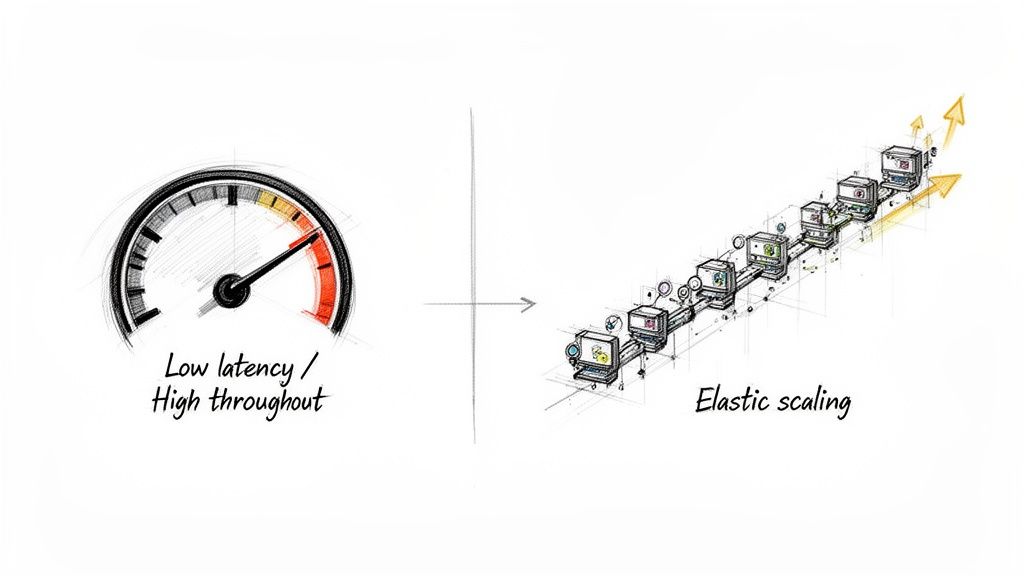

Performance and scalability are where the hardware load balancer vs software load balancer debate truly intensifies. This discussion is not just about raw speed; it's a deeper conversation about traffic patterns, growth plans, and your team's operational philosophy. You are choosing between the predictable, brute-force power of a dedicated machine and the flexible, on-demand agility of a distributed system. Hardware load balancers offer deterministic performance, meaning you get a consistent level of throughput and response time regardless of the activity on the application servers behind them. They achieve this using specialized ASICs that handle traffic processing directly in hardware, bypassing the general-purpose CPU.

Key Difference: Hardware load balancers scale vertically (buy a bigger box), while software load balancers scale horizontally (add more instances). This fundamental distinction impacts cost, agility, and your ability to respond to traffic spikes.

This setup is ideal for environments where every millisecond is critical and traffic volumes are consistently high. However, this strength is also a weakness. Scaling a hardware load balancer is a vertical process: you must purchase a bigger, more powerful box. This involves significant capital expense and a lengthy procurement cycle, making it unsuitable for applications with unpredictable traffic.

Software load balancers adopt a different approach. Their performance is tied to the commodity resources they run on—CPU, memory, and network I/O. Their real power lies in their ability to scale horizontally. When traffic surges, you simply spin up more instances of the software load balancer. This model is a natural fit for cloud-native environments built on elasticity and on-demand resources. Since they run on standard servers, you must monitor resource consumption, a key operational difference from the "set-it-and-forget-it" nature of hardware. You can learn more about this in our guide on how to check CPU utilization in Linux.

| Attribute | Hardware Load Balancer | Software Load Balancer |

|---|---|---|

| Performance Model | Deterministic, high throughput | Variable, dependent on underlying resources |

| Latency | Ultra-low, consistent | Higher, can vary with system load |

| Scalability Method | Vertical: Upgrade to a larger appliance | Horizontal: Add more instances on demand |

| Response to Spikes | Limited by fixed capacity | Highly elastic and adaptive |

| Best Fit | Predictable, high-volume workloads | Unpredictable, dynamic traffic patterns |

Analyzing Total Cost of Ownership and Management

When choosing between a hardware and a software load balancer, the initial price is just the beginning. To understand the true financial picture, you must consider the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO), which includes all direct and indirect costs over the solution's lifetime. The two options represent contrasting financial models: a traditional Capital Expenditure (CapEx) model versus a modern Operational Expenditure (OpEx) model. Hardware load balancers are a classic CapEx investment. You make a significant upfront payment for a physical device that depreciates over time. This initial purchase is followed by recurring costs, such as annual maintenance contracts, power, cooling, and the specialized network engineers required to manage the proprietary hardware.

Software load balancers, on the other hand, operate on an OpEx model that aligns with cloud-era finances. Instead of a large one-time purchase, costs are spread out as a recurring subscription or licensing fee. This pay-as-you-go approach offers greater financial flexibility. The primary costs are the license and the underlying compute resources—the virtual machines or containers hosting the load balancer instances. For a detailed breakdown of cloud-based costs, our guide on AWS load balancer pricing is a helpful resource. Management also shifts from dedicated network engineers to DevOps teams using Infrastructure as Code (IaC) tools like Terraform or Ansible, integrating the load balancer into automated workflows. You can explore more of these in our review of top cloud infrastructure automation tools.

Contrasting Deployment Agility and Cloud Integration

The difference between hardware and software load balancers is most apparent during deployment. One involves a deliberate, physical process rooted in traditional IT, while the other is a fluid, code-driven workflow designed for modern development speed. Deploying a hardware load balancer is a multi-week or even multi-month project involving procurement, physical installation (racking and stacking), and manual configuration by a network specialist. This entire lifecycle is slow and disconnected from the software development pipeline, creating a bottleneck for agile teams.

Software load balancers transform this physical process into a simple, automated action. A DevOps engineer can deploy one in minutes by launching a pre-built image or defining the resource using Infrastructure as Code. This code-based approach makes the lifecycle repeatable, consistent, and incredibly fast. Beyond deployment speed, software load balancers are purpose-built for cloud environments like AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure. They integrate seamlessly with the dynamic nature of these platforms. For instance, in a Kubernetes environment, a software load balancer deployed as an ingress controller can automatically detect and register new pods, enabling a level of dynamic control that hardware at the network edge cannot match.

| Integration Aspect | Hardware Load Balancer | Software Load Balancer |

|---|---|---|

| Deployment Method | Manual racking, cabling, and CLI configuration. | Automated provisioning via IaC (Terraform, Ansible). |

| Configuration | Static, managed by network teams. | Dynamic, managed as code by DevOps teams. |

| Cloud-Native Fit | Poor; sits outside cloud orchestration. | Excellent; integrates with Kubernetes, service discovery. |

| Lifecycle | Weeks to months for procurement and setup. | Minutes to deploy from code or marketplace. |

Making The Right Choice For Your Environment

Choosing between a hardware and software load balancer is a strategic decision that must align with your budget, team skills, and long-term goals. There is no single "best" answer; the right choice fits your architecture and business needs. It is a trade-off between raw, predictable power and operational flexibility. For some, the guaranteed high throughput of a physical appliance is essential. For others, the agility and pay-as-you-go nature of a software solution is the only viable path for growth and adaptation.

Key Decision Factors

- Performance Needs: Do you require predictable, ultra-low latency or elastic capacity that can scale on demand?

- Budget Model: Does your organization favor a large, one-time capital expenditure (CapEx) or a flexible, recurring operational expenditure (OpEx)?

- Environment: Is your infrastructure based in a physical data center, a public cloud, or a hybrid of both?

- Team Skills: Do you have specialized network engineers for hardware management or DevOps teams proficient in automation and IaC?

For a financial institution with a high-frequency trading platform, a hardware load balancer's deterministic performance and security are non-negotiable. For a fast-growing SaaS startup with unpredictable traffic, a software load balancer’s elastic scaling and OpEx model are a natural fit. An enterprise with a mix of on-prem legacy applications and modern cloud services might require a hybrid approach, using hardware for stable workloads and software for dynamic cloud environments. Answering these questions will point you to the solution that best supports your application and business. Safely validating any new setup is crucial, and you can learn more in our guide on how to test Nginx configuration.